Food Security

Over 2 billion people did not have access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food in 2020.

For decades, global hunger was on the decline. But now, due to conflict, climate change, global inequality, and other factors, the worst form of hunger – famine – threatens to return.

What is famine? A famine is defined as the most severe kind of hunger crisis. It’s very rare, but when it does occur, it means that there is an extreme shortage of food and several children and adults within a certain area are dying of hunger on a daily basis.

Some deadly emergencies happen suddenly, like earthquakes, floods, and other natural disasters. This is not the case with famine. A famine happens slowly, caused by long-term conflict, climate shocks, extreme poverty, and other drivers. Famines are never inevitable – they are always predictable, preventable, and man-made.

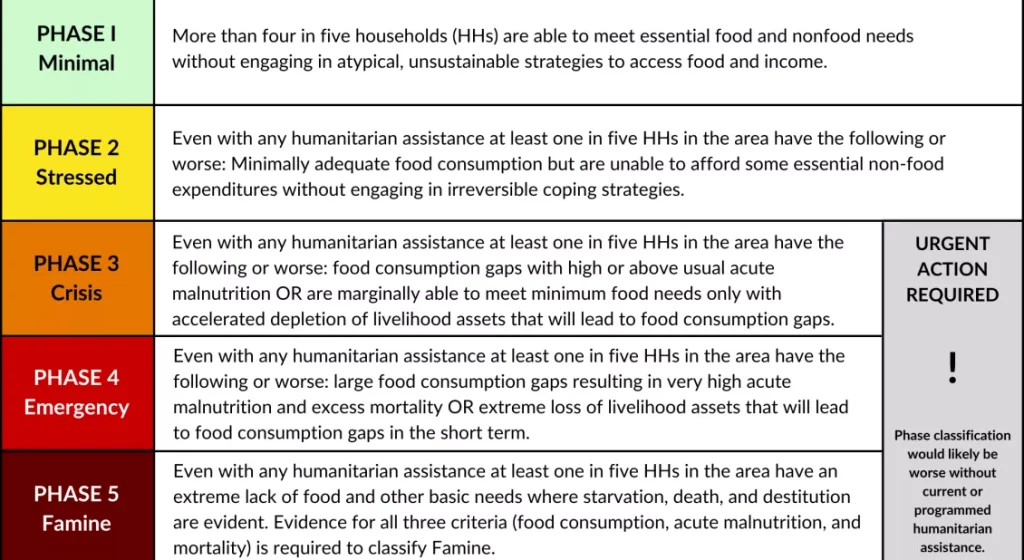

Famine is a technical term – it’s only officially declared when a series of specific food insecurity, mortality, and malnutrition criteria are met.

A famine is declared when:

To declare a famine, the world turns to the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) system, a framework involving governments, UN agencies, organisations like Action Against Hunger, civil society, and other relevant partners. Together, using the IPC’s scientific standards and analytical approach, partners classify the severity and magnitude of food crises in a country.

The IPC has five phases for hunger crises, ranging from Phase 1 (Minimal/None) to Phase 5 (Catastrophic/Famine), and each has its own set of technical criteria.

The key to understanding food emergencies is data – and a lot of it. Action Against Hunger and our partners carry out food security and nutrition surveys to gather information on food availability, malnutrition levels, and mortality rates.

All of the data is then collected and analysed, and IPC partners agree on the overall results and conclusions. If a country, or part of a country, meets famine (IPC Phase 5) criteria, then each partner – including the country’s government – must reach a consensus on these findings before famine is declared. At times, famine declarations can become political decisions, rather than humanitarian ones.

Before and after a famine is declared, the goal of the IPC system is to trigger action to prevent hunger crises from deteriorating further and to save lives. But, although it’s a very helpful tool, the system is far from perfect.

Often, the same conditions that cause hunger are the ones that make it incredibly difficult to gather the data needed to determine if famine is occurring.

Most people facing hunger in the world today live in countries affected by conflict.

There have been just two famines in the 21st century.

In 2011, in the midst of a severe drought and conflict, famine was declared in Somalia after an estimated 250,000 people died.

In 2017, after years of civil war, parts of South Sudan were found to be experiencing famine.

For months before both of these famines were declared, the United Nations and humanitarian organisations warned of the deteriorating humanitarian crises. Aid eventually came but, for hundreds of thousands of malnourished children and families, it arrived too slowly.

After many years of progress in the global fight against hunger, a combination of factors – conflict, climate change, and global inequality – has driven millions of people to the brink of starvation.

According to the United Nations, right now, an all-time high of as many as 49 million people in 46 countries could be at risk of falling into famine if they do not get urgent assistance. The countries at highest risk of famine in 2024 are Burkina Faso and Mali, South Sudan, Sudan and the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

While famine hasn’t been declared in these countries – and it may never be – the warning bells are now ringing, and the world must listen. We cannot wait for an official famine designation to take action to save lives.

Life-threatening hunger is predictable, preventable and treatable, so a world without it is possible. We tackle it where it hits and stop it. Whenever and wherever people need our help. More than that, we work to prevent it in the first place by leading research that will create a world free from hunger. Forever.

Over 2 billion people did not have access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food in 2020.

Rising temperatures and extreme weather are having a devastating impact on communities.

Poor nutrition threatens the growth and development of millions of children.