In Sindh, Pakistan’s third largest province, nearly half of children under five suffer from severe acute malnutrition – the deadliest form of hunger. Poverty, poor access to healthcare, a lack of clean water and failed harvests due to drought and flooding threaten the future of the country’s most vulnerable children.

The coronavirus pandemic is adding further strain in the region, risking the lives of even more children. Fear of the deadly virus, together with lockdown restrictions, mean many families are too scared to seek the vital treatment they need when their children become sick with hunger.

Fighting to keep our clinics running

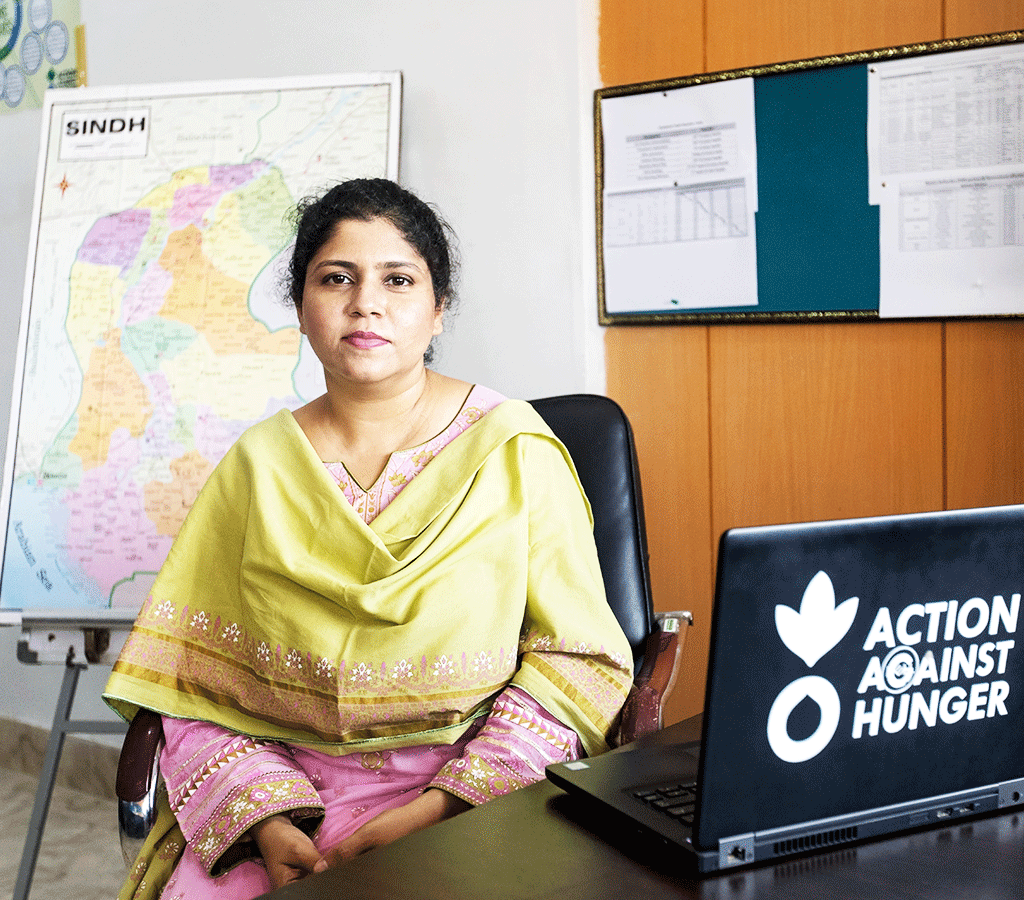

Dr. Ayesha Aziz runs the EU-funded Programme for Improved Nutrition in Sindh (PINS), supported by Action Against Hunger. Overseeing eight health centres and 262 outpatient clinics, she knew that nutrition services were vital – especially during a pandemic.

Dr Ayesha and her team worked tirelessly with local and national governments to make sure the centres stayed open to vulnerable families and that staff had enough PPE. She remembers how fear swept through communities when coronavirus emerged in Sindh.

“People had this fear of contracting Covid-19 if they would visit the health centres. People stopped visiting the hospital and our admissions reduced a lot.”

Seeking treatment in lockdown

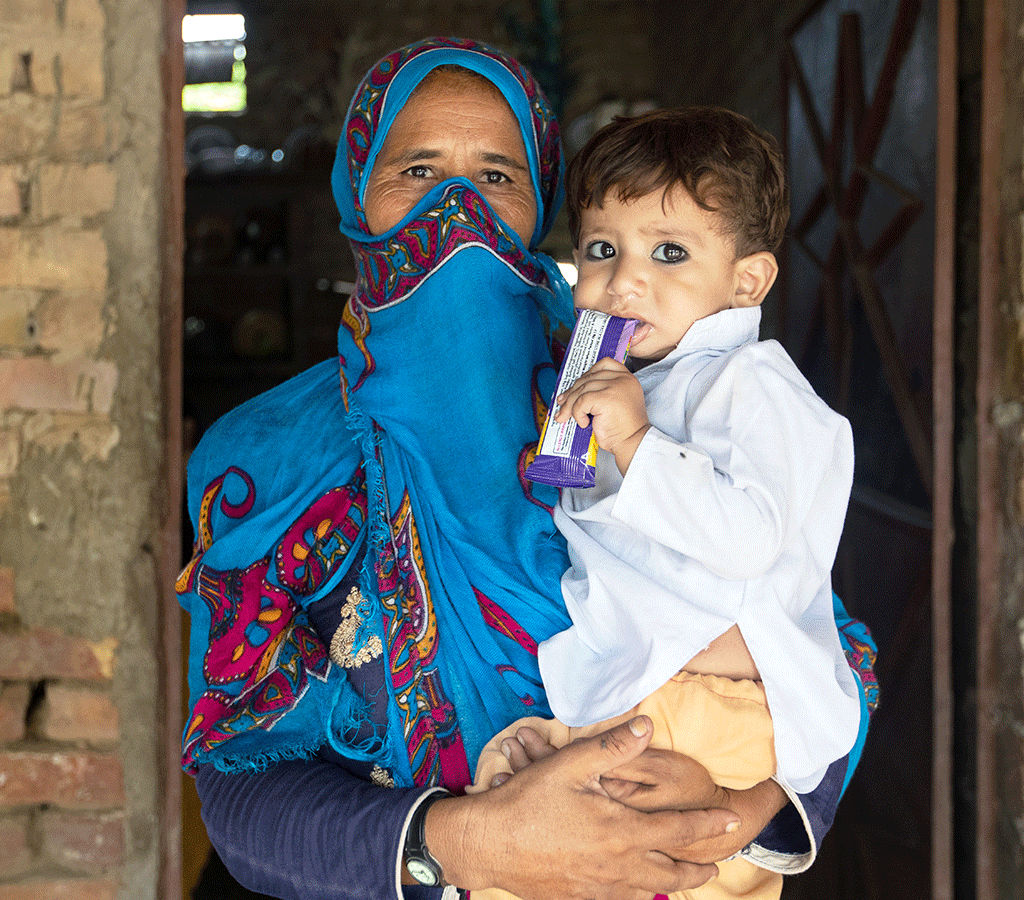

Kiran, mum to six-month-old Ruksana, was nervous about bringing her daughter to the clinic during the pandemic. But when Ruksana’s condition became critical, she felt she had no chance of surviving.

“My daughter had a fever and she was weak,” explains Kiran. “She was so sick that she wouldn’t drink milk or even cry.”

Despite coronavirus fears, Kiran made the difficult journey to the hospital, so her six-month-old daughter could receive the life-saving treatment she desperately needed.

“We heard good things about this hospital and that is why we came here. By God’s grace, the treatment is good here. Ruksana is feeling much better and has energy and colour in her face.”

Our health centres are a lifeline for children like Ruksana who need urgent medical care. Each one is equipped with trained medical staff as well as essential supplies, including ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) that brings a malnourished child back to good health again in just six weeks.

Dr Sohni Laghari is one of the medical officers who help children like Ruksana recover from life-threatening hunger.

“We have a six-bed ward that is currently full. Most of the patients we treat have malnutrition,” says Dr Sohni, explaining the situation at the hospital she works in. “Due to Covid-19, a lot of patients were facing problems in reaching us. We were provided with safety kits including sanitisers, gloves, masks etc… This helped us to continue our work easily.”

Going door-to-door to save lives

As part of the programme in Sindh, we’ve trained 2,800 community health care workers to support some of the hardest-to-reach communities. Our teams have continued to screen children for life-threatening malnutrition in their villages during the pandemic, quickly referring them for further medical treatment if needed.

This approach means we can regularly check up on children and advise mothers who are struggling to provide their children with nutritious, balanced meals. They also share vital information so communities can stay safe during the pandemic.

Noor is a mum of four, but her youngest son Taj was very weak when he was born. Her family have suffered a lot during the coronavirus pandemic, but they were able to access support thanks to an Action Against Hunger-trained community health worker.

“The community health worker told me about the centre. I got the medicine for my child and he is now getting better day by day. They also gave us information about coronavirus and taught us how to keep our home and children safe.”

Despite the coronavirus pandemic and lockdown restrictions, the PINS programme supported by Action Against Hunger has provided vital medical treatment for 70,000 children suffering from life-threatening hunger.